Race and Labor: An Introduction

- Stone by Stone

- Jun 22, 2018

- 3 min read

Updated: Jun 26, 2018

Caroline Waring

When you’re looking through our Spotlights tab, you’ll probably notice a glaring hole in our write-ups: an utter lack of black workers’ stories. For many workers, the construction of Duke’s West Campus was simply another job: underpaid, exhausting, and sweaty. Not everyone was afforded the same emotional investment or pride in the work. Throughout our research, we always found more black faces in the photographs of construction than could be accounted for in the University Archives’ material. No one interviewed the black laborers on the project or reported on the black stonemasons. In the University’s ledgers, black workers appear underrepresented—it is likely they were hired by other subcontractors on the project, so that even their names are lost to us.

When black workers are listed in the ledgers, they are frequently referred to as “helpers,” and largely worked as common laborers. A “carpenter helper,” for example, might have the same skills as a carpenter, but would not be licensed by the state and would receive a lesser pay. Although there were five black plumbers in Durham during 1942, the state refused to grant them licenses.¹ They were thus classified as "helpers," and considered not as fully qualified as their white, state-certified counterparts. In a similar case, there was only one black electrician in Durham during 1930, while there were 88 white electricians.² According to the historian Vernon Kiser in his 1942 thesis on African American labor in Durham, “It is difficult for [black electricians] to get a license to practice when trained. White boards find various ways to keep them out of employment.”³ Black workers were strategically kept out of skilled trades and leadership positions: in 1930, there were 1558 black laborers living in Durham, but only 132 white laborers.⁴ Yet the white laborers' stories are much more visible to us.

From historical documents and photographs, it’s clear that Duke's campus was built on underpaid black labor. Yet, when this labor is acknowledged by contemporaneous sources, it’s in patronizing and racist language. In preacher Garland R. Stafford’s autobiography, he remembers the Duke construction, and writes that: “Black men with mattocks, singing as they dug in rhythm, were digging up other areas for grass to be sown.”⁵ Unknowingly, this portrait of labor evokes the inextricable connection between plantation slavery (in its evocation of the racist minstrel persona) and the Jim Crow-era workplace.

Though it was rare, however, not all black workers in Duke construction were forced into low-paid, unskilled positions. Skilled black stonemasons worked alongside a wide-ranging group of white workers from North Carolina and immigrants from Ireland and Italy. Likely, this could only happen because these stonemasons were not unionized. According to Kiser’s thesis, “Unions very often keep the Negroes from securing work in [brickmasonry]. [Historian J.T. Taylor] said: 'White men often refuse to work side by side with Negroes, especially when both receive the same wages.'"⁶ Ironically, black workers could only access this workspace through the absence of an institution—the union—designed to provide laborers with hospitable and improved working conditions.

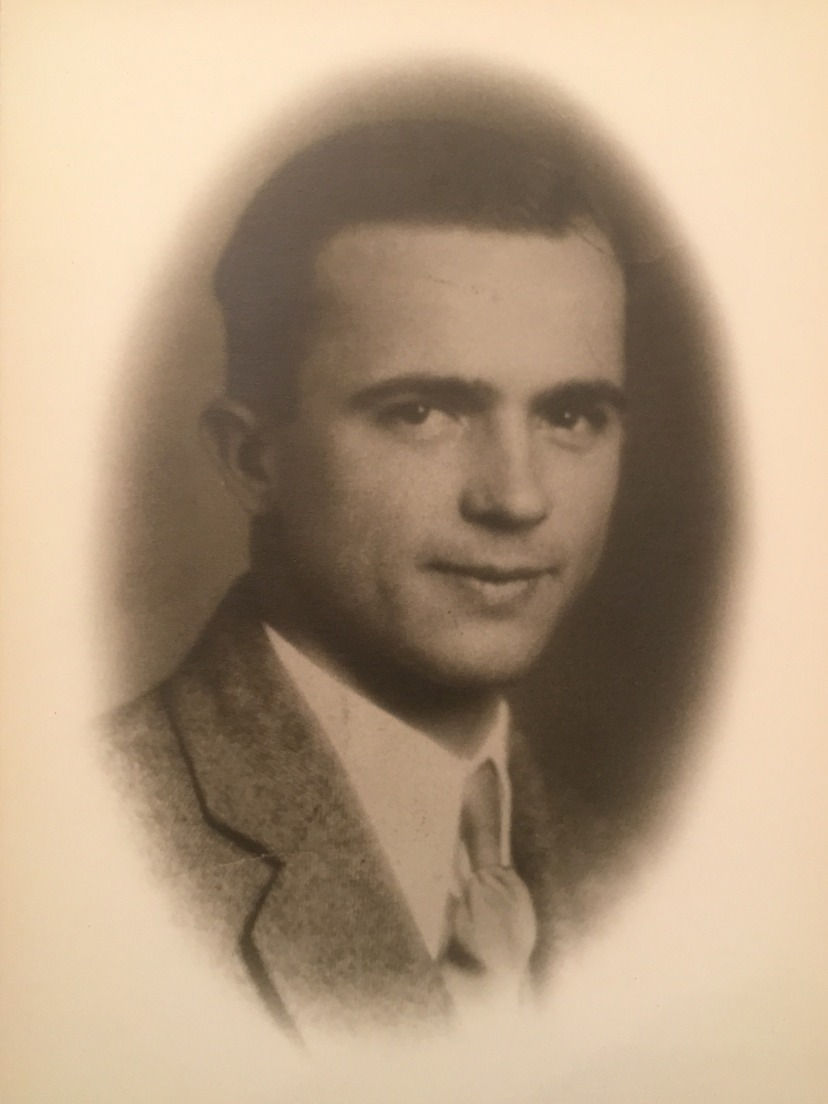

Yet the mark that black laborers left on this campus cannot go unacknowledged. Lucius Jeter, a black stonemason, gave decades to this school: he worked in Duke construction well into the 1950s.⁷ His contribution to the university eclipses that of the average student. West Campus—in all its stone, arches, and gargoyles—simply could not stand without its black workers.

1. Vernon Benjamin Kiser, "Occupational Change among Negroes in Durham" MA thesis, Duke University, 1942.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Garland Reid Stafford, Up the Years from Buffalo: An Autobiography, (Statesville, North Carolina: Bucolic Enterprises, 1994), 131.

6. Kiser, "Occupational Change."

7. "Lucius Jeter, circa 1954," Box 86, University Archives Photograph Collection, University Archives, Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University.

Comments